Peter J. Werth, President and Chief Executive Officer of ChemWerth, a US-headquartered full-service generic active

pharmaceutical ingredient (API) development and supply company providing

current Good Manufacturing Practices (cGMP) quality APIs to the regulated markets, shares his view on how the government inspections have evolved over the past years. The effect of the recent US Food and Drug Administration (US FDA) inspections is putting the global pharmaceutical supply chain in real danger. Excerpts from the interview.

Welcome back Peter. Let us start by talking about Jinan Jinda, a company you have represented for over 15 years, and that was placed on the FDA’s import alert list in 2015 and was recently issued a warning letter after a June 2016 inspection. What do you have to say about Jinan Jinda?

I still maintain what I said previously — Jinan Jinda Pharmaceutical is a good GMP factory which continues to produce stable, high quality, GMP APIs. Jinda continues to pass customer audits and meet all international quality standards.

After the concerns highlighted by European authorities in 2015, Jinan Jinda entered into a five-year service agreement with ChemWerth with the goal to further strengthen Jinda's quality system and GMP compliance.

The US FDA gave Jinan Jinda a warning letter based upon what they considered a breach in “data-integrity” and cited 90 batches of API that had a potential breach.

As part of the service agreement, we reanalyzed all the 90 batches and all 90 batches met the specifications. We reviewed their customer complaint file and found no quality-related complaints.

We found no relationship at all between data integrity and quality.

Their commitment to be a qualified supplier for the EU and the US regulatory markets has never changed.

Are you saying that both

European and US regulators made incorrect conclusions about the quality of

products coming out of Jinan Jinda?

There are many examples where the US FDA and European regulators have failed to agree on the state of compliance of the same facility and more importantly on the quality of products coming from those facilities.

Let me give you an example of FACTA Farmaceutici SpA in Italy, where FDA investigators uncovered data-integrity violations in multiple lots of sterile drug product. The original data showed failing results, while the final data (reportedly) showed passing results.

The FDA investigators also observed many copies of uncontrolled blank and partially-completed cGMP forms and also documented that employees at FACTA used paper shredders to destroy critical laboratory and production records.

While the FDA went ahead and issued a warning letter, an inspection performed exactly at the same time by the Italian regulators, had FACTA’s EU GMP certification renewed .

What does this say about the products coming from the facility?

In another example, Granules India which manufactures pharmaceutical formulation intermediates (PFIs) and finished dosage forms (FDFs) was inspected by the US FDA in October 2016 and the FDA had no observations.

Three months later, Portugal’s health authority — INFARMED — inspected the same site and based on observations related to granulation and primary packaging of tablets, the agency recommended the suspension and recall of certain batches supplied by Granules, from the market in Portugal.

A month after recommending the suspension, INFARMED issued a GMP certificate to Granules!

The disconnect is even wider when it comes to data-integrity violations which are uncovered in clinical research laboratories. The Europeans uncovered data-integrity concerns at GVK Labs in India and recommended the suspension of 700 different drugs. The FDA, on the other hand, found no cause of concern at GVK.

It is obvious that there is something wrong with the inspection system and the obsessions with ‘data-integrity’. It appears that making good quality APIs, following all the GMP compliance regulations and using the six system approach does not help factories pass FDA inspections.

In addition, ‘data-integrity only’ focused inspections are unfairly being handled as ‘For-Cause’ inspections by the agency when compared with firms that receive a routine six quality system inspection.

In many cases, these data-integrity focused inspections focus almost entirely on only one subset of data-integrity data — electronic laboratory data legacy systems. This is not only unfair but more importantly, it is short-sighted since such a limited scope inspection could very well miss ‘the real’ quality problems.

Take, for instance, product contamination issues from a production line. Can an intense ‘electronic data-integrity only’ inspection uncover an issue such as this? I think not.

How many patient health issues have been directly linked to electronic laboratory DI issues vs contamination issues? The answer is clear.

The system seems to be arbitrary and focuses on non-quality issues like data integrity, missing standard operating practices (SOPs), poor follow-up reports and other non-quality related issues.

We need to get the factories and the inspectors on the same page – like it was done in the good old days.

How can you defend Jinda’s product quality when the FDA in its warning letter had written that when an out-of-specification (OOS) unknown impurity peak was

obtained during stability testing, Jinda hid the presence of this impurity? And

when Jinda obtained failing results they tested new samples.

Jinda’s product quality problems are resolved/solved before the product is passed by their quality assurance/quality control. If there was an issue of unstable product, customers would have been recalling dosage form batches of the product supplied by Jinda to the marketplace.

There has not been even one instance where customers have rejected a batch of a product from Jinda. Or recalled a drug product from the market that uses API from Jinda.

With respect to re-testing of samples, the industry is facing a challenge which needs to be addressed. At ChemWerth we completely agree that it is wrong to be using the practice of repeat testing until a favorable result is obtained (also called testing into compliance).

However, regulators need to realize that chemists in labs have started getting scared of reporting “gross errors”. This fear is an outcome of the over-action involving data integrity by regulatory agencies. And this fear is preventing companies from documenting their actual problems.

The FDA should make data history the key to product quality and data integrity should be a small part of data history.

Read ChemWerth’s 18 reasons to delete analytical data

As a result, if you have a batch of API (this does not apply to finished formulations) that failed due to a lab error and has chemists now scared to report problems, regulators need to ask how unacceptable is the practice of re-testing?

‘API only’ manufacturers like Jinan Jinda are responsible for the product quality they ship to the dosage form manufacturer. The dosage form manufacturer, in turn, is responsible for the final quality of the API that goes into the dosage. The final dosage manufacturer has advanced equipment and well-trained analysts.

The dosage manufacturer will certainly reject poor quality batches.

Any product that does not meet specification would have been rejected and returned to the API manufacturer, and at a great cost. In this case, to Jinda.

There is no economic advantage and no good reason for the ‘API only’ manufacturer to delete or falsify data. They cannot cheat on the analytical testing and produce fraudulent COAs (certificate of authenticity), which makes data-integrity issues related to quality non-existent.

The FDA also cited concerns over Jinda’s staff being able to alter/delete electronic data and its failure to perform a comprehensive retrospective evaluation to determine whether appropriate corrective actions and preventive actions were identified and implemented for each OOS result obtained.

The FDA has a view on how things need to be remedied and Jinda made a commitment to hire a third-party consultant to rebuild its quality system by July 2018. The FDA’s warning letter highlights that their primary concern is Jinda’s lack of an interim plan to mitigate risk.

My view is that the US FDA’s focus should be on ensuring that the company produces stable, high-quality API. How valuable is a retrospective evaluation when the API has already been shipped, formulated into a drug product, supplied into the market and the finished drug has no quality problems?

The management of Jinda comprises of intelligent people who understand that repeat product quality deviations are bad business, both from a perspective of economics and reputation.

So what is the

way forward for companies like Jinda?

For the first time in more than 30 years of my being in business, FDA’s enforcement actions are putting the global pharmaceutical supply chain at risk as it is making the industry question the value of doing business with the United States.

Companies are getting tired of the expected continuous investment in compliance activities (e.g. user fees, investing in quality control equipment which complies with new regulations, engaging third-party consultants etc.) that effectively have almost no impact on improving product quality.

Factors such as the variability of inspection outcomes, increasing cost of doing business, and increasing pressure on drug makers to reduce the price of drugs, are making our clients in China and India mull over the value of continuous investments in compliance activities and how these are not related to quality.

It is worthwhile to mention that China and India are critical to the US drug supply chain, if the US is looking for continuous supply at competitive prices.

How do you

propose the FDA should review manufacturing compliance?

Plant inspections are complicated exercises prone to human variability and subjectivity.

While important, API plant inspections should act as a compliment to product quality, and not the other way around.

Regulators need to increase their efforts in defining API product quality. Because if they do not know or cannot clearly define a quality product, how can they effectively inspect the operations of plants.

In addition, the conversation needs to be moved from data-integrity violations to preserving data history, something I have spoken about in the past.

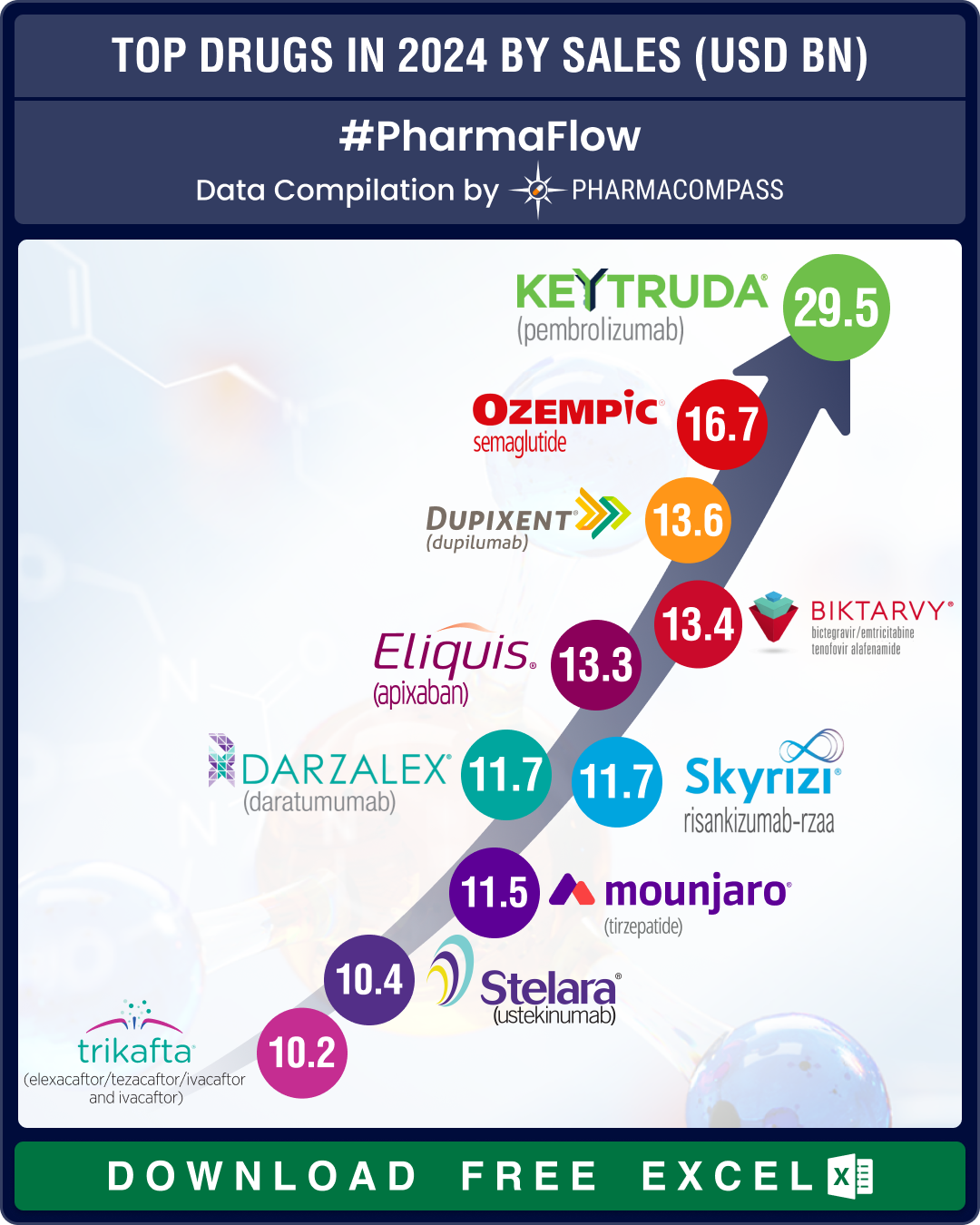

The PharmaCompass Newsletter – Sign Up, Stay Ahead

Feedback, help us to improve. Click here

“ The article is based on the information available in public and which the author believes to be true. The author is not disseminating any information, which the author believes or knows, is confidential or in conflict with the privacy of any person. The views expressed or information supplied through this article is mere opinion and observation of the author. The author does not intend to defame, insult or, cause loss or damage to anyone, in any manner, through this article.”